Financial Health is Public Health

Written by Jason Q. Purnell, Washington University in St. Louis“If you want to lower my blood pressure, help me pay my electricity bill.”

That statement from a resident of Rochester, NY, has remained with me for several years because it so intuitively speaks to the connection between financial health and physical and mental health. When the American Psychological Association released the results of its “Stress in America Survey” in early 2015, money topped the list of worries, ahead of work, family, and health issues. Seventy-two percent of adults worried about money “at least some of the time,” and 26 percent worried about their finances “most or all of the time.” The connection of financial stress to health is quite explicit in the survey results, with nearly one-third of respondents who say that struggling to get by financially affects their ability to lead a healthy lifestyle, and more than 20 percent who say that they have either considered or have skipped medical visits because they lacked the financial resources. Not surprisingly, adults with lower incomes experience financial stress more acutely, and those who experience high levels of stress related to their finances are more likely to cope by smoking, eating, drinking alcohol, and watching television in excess, all of which increase their risk for chronic conditions like diabetes and heart disease.1

It isn’t just adults who suffer the consequences of stress when money is tight. Groundbreaking research reviewed in a 2011 report from the American Academy of Pediatrics finds that childhood exposure to poverty and stress has both immediate and long-term effects on development, behavior, and health.2 Scientists have identified differences in the structures and functioning of the brains of children in poverty, making them more sensitive to even mildly stressful situations and less likely to be able to learn new information.3 Children who experience a particularly severe type of stress called “toxic stress” are also at increased risk for negative behavioral and health outcomes as adolescents and adults.

Though commonly thought of as a purely subjective experience of feeling overwhelmed by life’s demands, stress is a complex set of physical processes that start in the brain and extend throughout the body’s various organs and systems. In the face of mild-to-moderate, isolated and short-lived periods of stress, this response is quite adaptive. It helps us to focus the mental and physical resources necessary to either confront or escape threatening situations. However, when there are multiple sources of severe or inescapable stress, the stress response essentially never turns off, and the body begins to break down. The immune system is compromised, inflammation increases, and the ability to adapt to future stress is disrupted. This is why children who are exposed to abuse, neglect, domestic violence, unstable caregivers, and mentally ill or incarcerated members of their households — all examples of what are called “adverse childhood experiences” by an eponymous study — are at greater risk for social, emotional, and health problems well into adulthood. These children are also more likely to take up risky behaviors as a means of coping in adolescence and adulthood, such as smoking, drug use, overeating, problem gambling, and unsafe sexual practices.4 This exacerbates the harm that toxic stress placed on their bodies as young children. When these young people become parents, the cycle often continues.

Stress and its related impacts are part of a broader concept in the field of public health called the “social determinants of health.” The World Health Organization defines social determinants of health as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age” that are “shaped by the distribution of money, power, and resources at global, national, and local levels.” We know that both health behaviors (e.g., smoking, leisure-time physical activity, cancer screening) and health outcomes (i.e., disease, disability, and death) follow a general pattern by which those with incrementally more education, income, and wealth also have incrementally better health. This “socioeconomic gradient in health” not only influences individuals and families, but also the health and vitality of communities and nations.

The Wealth (and Health) of Nations

The United States is the wealthiest country in the world, with a gross domestic product of nearly $17 trillion, between 17 percent and 18 percent of which is spent on health care. Yet our health lags that of other wealthy nations.5 The poor showing is the result of more limited health care access and affordability; riskier behaviors such as high-calorie diets, drug use, and violence; physical environments that discourage physical activity; higher rates of child poverty; greater income inequality; lower economic mobility; and a weaker social safety net. Our outcomes can’t be explained away by our diversity or blamed entirely on the poor. Even white, college-educated, high-income adults with health insurance have worse health outcomes than their similarly situated peers in other nations.

Simply providing more and better health care is unlikely to solve the problem of health disparities. That means that even legislation hailed as the most momentous social policy in at least a generation, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), is not sufficient to the task of alleviating persistent health inequality. Although the ACA gives significant nods to prevention and population health, its central provisions — expanding health insurance coverage to millions of Americans — are not expected to significantly change the outlook for health disparities, if evidence from similar reform in the State of Massachusetts is any indication.6 One simple explanation for why this might be the case comes from the United Kingdom, which has had universal access to health care since the 1940s. The landmark Whitehall Studies of British civil servants find a clear link between employment class or rank of civil servants and health. Those in higher-status jobs enjoyed better health and longer lives than those lower down the employment scale. Even in a country with universal health care, health inequality remains.

Under the best of circumstances, the ACA will not achieve universal coverage, and the decision of the Supreme Court to allow individual states to decide whether to expand Medicaid means that many disadvantaged adults will continue to go without insurance coverage. Health care alone is not enough to change disparities, particularly in premature death, because its contribution to the explanation of such deaths is only 10 percent. That is because the contribution of medical care to the overall explanation of premature death in the United States is estimated at only 10 percent. The other 90 percent is a matter of lifestyle behaviors, genetics, social circumstances, and environmental exposures.

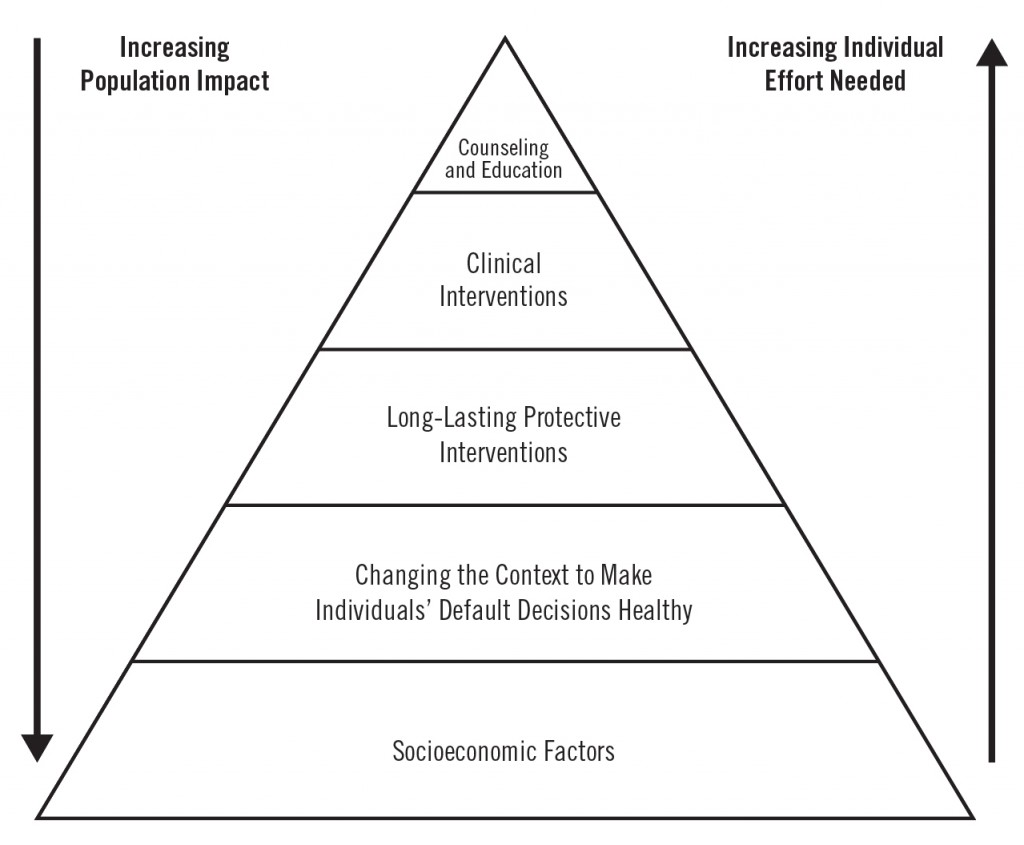

Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has another way of describing the relative influence of different kinds of interventions on the health of the population. He calls it the “Health Impact Pyramid” (Figure 1).7

At the top of the pyramid are interventions that have the smallest total impact on population health. These are familiar counseling and education activities, such as helping patients with diabetes monitor their blood glucose and eat a healthy diet. At the next level are interventions such as medications to control blood pressure and cholesterol, much of what we think of as at the heart of medical care. This set of activities still has a relatively small impact on population health. “Long-lasting protective interventions” have a larger impact, and include immunizations against disease, certain cancer screenings, and smoking cessation programs. The bigger impacts come from changes in the environment that make healthy decisions easier, such as adding fluoride to the water supply to prevent cavities or removing lead from paint. These are interventions that protect people from potential threats to health without their having to exert much energy to benefit from them. At the very bottom of the pyramid are social and economic factors such as poverty, education, and adequate housing. These most fundamental resources also have the largest overall impact on health. As Frieden notes, they are also the most politically difficult to address. Indeed, it is at the nexus of culture and politics where the battle for America’s financial, physical, and mental health must be fought.

Necessary but Not Sufficient

Individualism is a guiding ethic in America, and it provides the lens through which many interpret societal outcomes. Even among those with the most glaring disadvantages, a strong moral sense of personal responsibility for one’s lot in life pervades. Nothing delights the American public more than heroic efforts to assume such responsibility in the face of very difficult circumstances. An early 2015 news story featuring a 56-year-old Detroit factory worker who walked more than 20 miles a day to and from work inspired a national outpouring of generosity totaling more than $350,000, including a new car worth $35,000. The flipside of this giddy support for individual heroism is a tendency to very quickly blame individuals or groups who are struggling for their lack of personal responsibility. In a nation in which nearly three-quarters of adults worry about money at least some of the time, where income and wealth inequality are at all-time highs, and where the rate of child poverty is among the highest in the developed world, it is fair to ask whether individual effort can be the total answer to what literally ails, and ultimately kills, Americans.

There is a turn of phrase in science: Conditions can be “necessary but not sufficient” for a particular effect or outcome. For example, water is necessary but not sufficient for ice. No matter how much one may will or wish it to be otherwise, water will not become ice unless it is exposed to a temperature at or below 32 degrees Fahrenheit. In a similar way, individual effort is necessary but not sufficient for what we commonly define as aspects of a successful life: completing education, holding a job, starting and sustaining a family, supporting oneself in retirement and throughout old age. Think of individual effort as the water in this scenario. The average person cannot hope to achieve any of these outcomes without a significant amount of effort, perseverance, and determination — all of which is absolutely necessary, but not sufficient. Young children do not raise themselves nor do they determine their parents’ marital status, education levels, or annual incomes. Vaunted though meritocracy may be as an ideal, many people get their first and subsequent jobs through networks of connection rather than laboriously wading through job postings. And a whole host of policies prop up the economic well-being of the relatively well-to-do, from home mortgage deductions to tax-deferred college and retirement savings accounts. Think of these and a multitude of other factors as the freezing temperatures, the context in which the “water” of individual effort is transformed into the “ice” of individual benefit — not merely material benefit, but the very length and quality of life itself.

Despite stacks of studies showing that financial health and physical and mental health are connected and that the conditions in which we live also affect how well and how long we can expect to live, the description above of how individual effort interacts with environment and resources to produce life outcomes remains a tough sell in the current political climate. We are told that the poor and the wealthy alike have gotten what they “deserved” by virtue of their individual successes and failures alone. Even providing health insurance to more Americans is controversial, in part, because it suggests that government is doing what individuals ought to be doing on their own. Either we continue down an unhealthy and ultimately untenable path of ever-increasing health care expenditures for suboptimal and unequal outcomes, or we somehow change the trajectory by changing the way we deliver the message. The latter of these alternatives is the path of a growing number of public health professionals who are convinced by the data supporting the power of the social determinants of health, but also aware that the public and policymakers may not be. In fact, they may not even be aware that the relationships between factors such as household financial status, education, and health are as strong as they are, and that is not their fault. Academics and public health and medical professionals are pretty adept at talking to one another, but their efforts to communicate information clearly and convincingly to the lay public often leave much to be desired.

New models are needed for translating information about the social and economic determinants of health for decision makers from parents to politicians. This was the argument made in a paper in the Annual Review of Public Health in early 2015.8 In it, lead author Dr. Steven Woolf and his team at the Center on Society and Health at Virginia Commonwealth University and my team and I at Washington University in St. Louis offered a framework that includes rigorous research as its basis, but also places emphasis on strategic forms of communication, a thorough understanding of the decision-making context, particularly for policymakers, and thoughtful engagement with key stakeholders. We use as examples of this framework the Education and Health Initiative, a national project led by Dr. Woolf’s center, and a local project I lead to improve the health and well-being of African Americans in St. Louis called For the Sake of All. Although developed separately, each initiative uses the full arsenal of modern communications, from policy briefs and reports to websites, YouTube videos, Twitter feeds, and blog posts to tell the story of how social and economic factors are affecting the health of ordinary individuals. We have some early evidence that the approach is working, or at least that people are talking and thinking in new ways about these issues. The response as measured by web traffic, social media mentions, and local, national, and even international media coverage suggests that this work has hit a nerve. Whether that can translate to changes in policy remains to be seen.

At a recent American Public Health Association meeting to discuss that organization’s goal of making America the “healthiest nation in a generation,” advanced medical technology was hardly mentioned at all. That was not because any of the speakers (including myself and Dr. Woolf) had a bias against medicine or truly life-saving scientific discoveries made every day. Rather, it was because the speakers recognized the wisdom of that simple statement by the man from Rochester. If we want to help people to live full and healthy lives, we must attend to their livelihoods; to the resources that make life possible from the very earliest stages of development to the waning days of old age. We must invest in interventions that address such things as high-quality early childhood development and that provide support for families at all income levels to accumulate and preserve assets. We must redouble our efforts to ensure that all children receive excellent elementary and secondary education and that the most vulnerable children receive the mental and physical health, social, and other services to help them succeed. Those children will also need support in completing postsecondary education and finding jobs with wages that will sustain them and their families, along with a set of benefits such as family and sick leave, retirement savings, and yes, affordable health insurance. And we must not only invest in individuals. We know that poverty, violence, and inadequate resources, services, and amenities affect the health of communities as well. We must find creative ways of making health promotion a central part of community and economic development. In these and many other ways, the inextricable, often stress-laden link between financial well-being and physical and mental health must become the centerpiece of public understanding and public policy. Both our economic health as a nation and the very lives of the American people depend on it.

NOTES

- American Psychological Association, “Stress in America: Paying with Our Health.” (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, February 4, 2015).

- Jack P. Shonkoff, Andrew S. Garner, and The Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, & Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, “The Lifelong Effects of Early Childhood Adversity and Toxic Stress,” Pediatrics 129 (1) (2012): e232–e246.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- In fact, a recent report from the Institute of Medicine found that the U.S. fares worse than many advanced economies on a long list of outcomes, including low birth weight and infant mortality; life expectancy at birth; injuries and homicides; teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted disease; HIV/AIDS; obesity; diabetes; heart disease; disability; and chronic lung disease. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2013). U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Panel on Understanding Cross-National Health Differences Among High-Income Countries, Steven H. Woolf and Laudan Eron, Eds. Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, and Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Danny McCormick et al., “Effect of Massachusetts Healthcare Reform on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Admissions to Hospital for Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions: Retrospective Analysis of Hospital Episode Statistics,” BMJ (2015) 350:h1480; Brian D. Smedley, “Moving beyond Access: Achieving Equity in State Health Care Reform,” Health Affairs 27 (2) (2008): 447–455.

- Thomas R. Frieden, “A Framework for Public Health Action: The Health Impact Pyramid,” American Journal of Public Health 100 (4) (2010): 590–595.

- Steven H. Woolf et al., “Translating Evidence into Population Health Improvement: Strategies and Barriers,” Annual Review of Public Health 36 (2015): 463–482.