The Real Financial Lives of Americans

Written by Jennifer Tescher, Center for Financial Services Innovation; Rachel Schneider, Center for Financial Services InnovationThat financial fragility is not simply a result of the recession. Stagnant wages, historic levels of inequality, and technology’s role in disrupting labor markets are all trends that grew slowly and quietly but have since caught the country’s attention with the spectacular plunge precipitated by the financial crisis. It was easy to miss the growing financial pressure on American families during the last 25 years, in part because consumers were masking their problems with unsustainable levels of debt. It was also easy to miss the growing fragility because of the lack of systematic analysis of the inner workings of households’ day-to-day financial systems.

A new body of research offers fresh and powerful insights into the real financial lives of Americans — their needs and aspirations, the choices they face, the networks and resources available to them, and their outlook. The data present a revised diagnosis of the financial pressure that families face and suggest that policymakers and practitioners alike must redefine what financial success means to better align the ways in which they try to advance financial success with consumers’ actual expectations and goals. We believe that what Americans want, and what policmakers and practitioners should help them to achieve, is financial health and well-being. Developing a shared definition and metrics for financial health is a crucial first step toward moving the country in this direction, and creating a standard by which to hold policymakers and practitioners accountable for improving the financial lives of Americans.

The Real Financial Lives of Americans

Meet Sarah and Sam Johnson. The Johnsons live in Ohio, in a small town near Cincinnati. Sarah is 38, and Sam is 49, and this is a second marriage for both. Sarah works full-time as a human resources assistant and part-time as a secretary. Sam sells electrical equipment, and he also coaches sports and works weekends at a call center. They support their daughter, Amy, age 8, and two grown children from prior marriages. Their son Matthew, age 20, is a full-time student living with them, and their daughter Anne, also 20, lives with them part-time but plans to move.

By their annual income, things look promising for the Johnsons. They have multiple sources of income and earn between $55,000 and $60,000 a year, just above the U.S. median. They own a house and two cars, and they have a 401(k) retirement account and health insurance. They have a bank account and credit cards, and they pay their bills online. They spend money on clothes, entertainment, and celebrating important events in their children’s lives.

Yet beneath the surface, the Johnsons are struggling. Despite working multiple jobs and receiving college financial aid, their monthly income is volatile and its timing and frequency is irregular. Their bills’ due dates, however, do not fluctuate accordingly. To make matters more complicated, their expenses fluctuate significantly from month to month. With this level of financial uncertainty, the Johnsons have been unable to put aside even a small cushion of savings for unplanned events, like the leaky roof they had, or the income reduction they faced when Sam went on short-term disability while recovering from foot surgery.

How do they cope? Some months they economize by downgrading the amount and quality of the food they buy. Some months they pay their mortgage and car loan instead of the light bill or phone bill. Some months they turn to credit cards, and as a result they have accumulated more than $3,000 in debt across seven cards. When asked to name their greatest financial aspiration, the Johnsons said, “To be able to pay our bills on time.”

While Johnson isn’t their real name, and some of the details of their story have been changed to protect their identity, their situation is real. They are one of the 235 families that participated in the path-breaking U.S. Financial Diaries project, a joint venture led by Jonathan Morduch of New York University’s Financial Access Initiative and Rachel Schneider of the Center for Financial Services Innovation (CFSI). As the U.S. Financial Diaries show, the Johnsons’ story is all too common.1

The 2015 Consumer Financial Health Survey conducted by CFSI provides a representative snapshot of the struggle American households face:

- 26 percent of Americans say their finances cause them significant stress.

- 43 percent struggle to keep up with bill payments.

- 36 percent are not confident they could come up with $2,000 in the next month for an emergency.

- 30 percent are carrying an unhealthy amount of debt.

Although the struggle cuts across income, age, race and ethnicity, black and Hispanic households of all incomes are struggling more than others:

- 19 percent of black households and 24 percent of Hispanic households are highly satisfied with their present financial condition, compared with 34 percent of white households.

- 35 percent of black households and 40 percent of Hispanic households find themselves always living paycheck-to-paycheck, compared with 29 percent of white households.

- 41 percent of black households and 48 percent of Hispanic households are confident they can meet their short-term saving goals, compared with 54 percent of white households.

In short, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts, American households are “savings limited, income constrained, and debt challenged.” Pew’s 2015 study, “The Precarious State of Family Balance Sheets,” showed that 70 percent of U.S. households face at least one of these three challenges, and more than one-third face two or even all three at the same time.

New Data, Revised Diagnosis

We know more about the financial challenges Americans face because of the emergence of several new data sources that are helping paint a more complete, nuanced and complex picture. The Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Household Economic Decisionmaking (SHED) captures a snapshot of the financial and economic well-being of U.S. households, the financial issues they face, and perceived risks to their financial stability. CFSI’s Consumer Financial Health Study (CFHS) focuses on consumers’ financial behaviors, attitudes, preferences and use of financial services, and uses the data to segment households by their level of financial health. Pew’s Financial Security and Mobility project studies how families’ balance sheets relate to both short-term financial stability and longer-term economic mobility. The U.S. Financial Diaries (the Diaries) analyzes extremely detailed data on the financial activities of 235 low- and moderate-income households over the course of a year to understand how they manage their daily finances. The inaugural report of the JPMorgan Chase Institute, “Weathering Volatility: Big Data on the Financial Ups and Downs of U.S. Individuals,” analyzes proprietary data to determine how customers’ income and consumption fluctuated monthly and yearly.

This research differs from other data sets, such as the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finance (SCF), in a few important ways. The SCF is designed to shed light on what households own and how much they owe in order to analyze trends in net worth. Given that assets are not evenly distributed, the survey oversamples wealthy households, which are most likely to own assets. In contrast, much of the research described above is intended to shed light on an array of household behaviors, decisions, and attitudes that are precursors to net worth — day-to-day cash flow, for instance, or subjective matters such as stress, satisfaction, and confidence. In several of these studies, researchers oversampled households in lower income quartiles to ensure a full picture.

Together, this new body of work creates a different lens on the financial lives of American households. What emerges suggests a set of revised diagnoses of the financial concerns facing Americans and new strategies for treatment.

1. Cash flow is as important an indicator as annual income

The Johnsons’ annual tax returns don’t tell their whole story. For that, it is necessary to also look at their pay stubs. Their monthly income fluctuates dramatically over time, from about $4,100 to nearly $9,000. The causes are numerous. Sam received only two-thirds of his regular pay while he recovered from his foot surgery. Both Sam’s and Sarah’s part-time jobs pay irregularly. Sarah’s ex-husband pays child support sporadically. Sarah and her son are both attending college, and they both get financial aid, but it arrives in lump sums irregularly during the year.

Income volatility is not a new phenomenon for families, but it is getting more attention lately. Research on the evolution of household income volatility by economists Karen Dynan, Douglas Elmendorf, and Daniel Sichel estimates that American household incomes became 30 percent more volatile between the early 1970s and the late 2000s. Income spikes and dips were commonplace for the families in the U.S. Financial Diaries. Their income had, on average, two and a half spikes and dips — defined as a 25 percent deviation from the norm — for a total of more than five months during the year in which income was materially different from the norm.

Other research has documented this same trend. Pew’s Financial Security and Mobility study showed that, in any given two-year period, nearly one-half of households surveyed experience an income gain or drop of more than 25 percent. The Federal Reserve’s SHED study found that 21 percent of respondents occasionally experience months with unusually high or low incomes, and 10 percent said that their income varies quite a bit from month to month. Monthly income volatility is more common than annual fluctuations. The JPMorgan Chase Institute “Weathering Volatility” report shows that 84 percent of individuals experienced at least a 5 percent change in their monthly income, compared with 70 percent of individuals who experienced such a change annually. Lower-income households’ incomes are particularly volatile. The Diaries found that one-half of households at or below U.S. poverty thresholds had trouble predicting their income during the month, compared to approximately one-fourth of households with incomes greater than twice the poverty threshold.

Complicating matters more, expenses can be as uncertain as income. For the Johnsons, only 20 percent of their monthly expenses are fixed. Over the course of seven months, their monthly expenses varied from $4,660 to $11,000. The $11,000 month included a new, more reliable car for work, a roof repair and clean-up of related water damage. The water damage aggravated their daughter’s asthma, so they had to replace the furniture and buy an air purifier.

Invariably, the income and expense shocks do not arrive in tandem, compounding the challenge. For Diaries families, about 60 percent of spending spikes were not accompanied by an income spike in the same month. One-quarter of expense spikes occur when a household’s income is below its median income. When families have access to savings or credit, the mismatch between income and spending can be accommodated. But for households without that slack, a mismatch is a source of anxiety and challenge.

2. Income matters, but so do planning and saving

The lack of wage growth in the United States is well documented, and a major challenge. Yet more income does not necessarily translate into financial success. Consider households with incomes over $100,000. According to Pew’s Mobility research, 22 percent say they do not feel financially secure, 12 percent have less than $10,000 in non-housing wealth, and 10 percent have no savings.

The CFHS documents similar conditions. One-third of households making more than $100,000 fall into either a coping or vulnerable segment, while two-thirds are healthy.2 In contrast, approximately one in five households earning less than $30,000 are healthy, as are 39 percent of those earning between $30,000 and $60,000.

Making more money certainly has some effect. For instance, 40 percent of CFHS households earning less than $25,000 a year say they “worry all the time about being able to meet monthly living expenses,” compared with 15 percent of households earning more than $100,000. Higher income is associated with less financial worry, but more income does not always eliminate worry.

Besides income, what else affects financial health? Planning, saving, and time horizon are most important. A long-term orientation is also key. Households that plan ahead for large, irregular expenses are 10 times more likely to be financially healthy than those that do not. Households with a longer savings time frame (five or more years) are 8 times more likely to be financially healthy than those whose savings time horizon is less than five years. Although households with higher incomes were more likely to be financially healthy, planning is much more predictive of financial health than income.

Against that backdrop, the Johnsons’ experience is the norm. It seems likely they would describe themselves as struggling. They work very hard at multiple jobs and earn more than the U.S. median, but none of that mattered when their old car started malfunctioning and their roof sprang a leak.

3. Access to financial services is important but insufficient

A growing awareness of Americans’ financial challenges has galvanized financial service providers and policymakers to design strategies to increase access to bank accounts and reduce use of “alternative” products and services like check cashing and payday loans.

However, the CFHS data show that bank account ownership alone is no guarantee of broader financial success. A little more than one-half of survey respondents with a checking or savings account are in the coping or vulnerable groups, in part because nearly one-third have an unhealthy amount of debt. Similarly, a savings account is not synonymous with saving. Approximately one in five savings account holders have less than $1,000 in savings, and slightly more than one-half have no plan for saving regularly.

Consider the Johnsons. They have a checking account, a mortgage, two car loans, seven credit cards, student loans, a retirement savings account, and employer-sponsored health insurance. They also have $3,000 in credit card debt, $8,300 in medical debt, and little savings beyond their retirement accounts. Access to financial services is useful for them, but it is not solving their core financial challenges.

4. Borrowing and saving are opposite sides of the same coin

Borrowing has long been frowned upon, while saving has long been praised. Yet people still choose to borrow, rather than spend their savings. In the CFHS, 39 percent of households say they sometimes leave a balance on their credit cards instead of using savings to pay it off. The SHED survey asked respondents a hypothetical question about how they would allocate an unexpected $1,000 of extra income. On average, respondents said they would spend $227, save $395, and pay down $377 of debt. More than one-fourth of respondents who reported saving some of their income said they were saving to pay down their debt.

Why do people borrow when they have money saved? Sometimes they need more than they have saved. Other times, they do not want to deplete their reserves. They like the idea that they will still have savings in case of an emergency. Some people borrow to repair or build their credit histories. Others use borrowing as a commitment mechanism to continue to build up more savings. In short, the cheapest possible access to funds is not the sole determinant of why people choose to borrow or save, though that is often how traditional economists expect them to make financial decisions.

In fact, both borrowing and saving are simply ways to stretch money by turning a large purchase into a smaller set of more manageable payments. The difference is that saving is free (or sometimes, interest-bearing) and provides the peace of mind that comes with knowing the funds have been socked away for the future, but it requires the self-discipline of accumulating the funds first. In contrast, borrowing allows more immediate gratification and the ability to build a credit history, but comes with a fee and with the potential anxiety of a future obligation. When deciding when to borrow or save, people appear to take both the psychological cost and the financial cost into account.

That is certainly the case for the Johnsons. Sarah says that she would never have been able to save up for the down payment for their house. Coming up with $20,000 would have been too daunting. However, the seller let them accumulate the down payment over 18 months, bundling the payments into their rent while they lived in the house. This converted their savings activity into an obligation like a debt, and gave them access to mortgage credit that would otherwise have been unattainable.

5. Financial progress is complex, unpredictable, and often messy

The financial lives of Americans are often characterized as linear trajectories “up the ladder.” When you’re young, you accumulate debt, which you pay down as you accumulate wealth over time. But rarely do individuals’ lives conform to these neat, stepwise progressions.

Households experience many fluctuations in their wealth, and significant life events can create road bumps in people’s financial lives. For instance, nearly one-third of Americans fell below the poverty line between 2009 and 2011, according to a 2014 Census Bureau report, but only a fraction of them stayed there for the entire three-year period. In “Americans’ Financial Security; Perception and Reality,” Pew reports that six in ten households experienced a financial shock in the prior year, such as a drop in income, a hospital visit, the loss of a spouse or partner, or a major car or home repair. Slightly more than one-half of this group report that the shock made it hard for them to make ends meet. That was particularly true for those making less than $25,000 a year (73 percent), but even for those making more than $100,000 a year, 34 percent felt financial strain.

The Johnsons exemplify the ups and downs families face. Earlier in her life, Sarah had filed for bankruptcy because of credit card debt. By the time she and Sam joined the Diaries study, they had resolved their credit issues enough to qualify for a mortgage and buy their home. After the study, however, Sarah filed for bankruptcy again. This time, it was because she had too many medical expenses.

Practitioners tend to look at household savings balances over time and are disappointed to not see steady growth. During a six-month period, however, the Johnsons’ account balance fluctuated between $250 and $8,600. Their experience is typical. Looking at point-in-time savings balances or expecting a constant upward trajectory misses the fact that people are indeed saving. They are just then spending and saving again in short, frequent intervals.

Defining the Ultimate Outcome

The financial challenges facing Americans are bigger and broader than previously understood. While the FDIC identifies 68 million Americans who are unbanked or underbanked, the CFHS identifies 138 million Americans who are financially challenged. Moreover, families like the Johnsons demonstrate that consumer behavior does not always conform to standard economic theories. Behavior that traditional economists view as “irrational” turns out to be quite rational given people’s circumstances and the available choices. When thinking about spending, saving, and borrowing, people are not simply choosing between now and later. The Diaries help us see that “soon” — such as the bill that is due next month — also matters and may influence behavior more than the prospect of putting money away for a distant future. Finally, understanding how households are faring financially is a more complex exercise than was previously appreciated. Though the data help paint a more nuanced picture, they do not suggest the path forward.

Nonprofit practitioners in the asset-building and financial capability fields see these new realities from their positions on the frontlines. As described in the opening essay by Andrea Levere and Leigh Tivol, many have been experimenting with a range of initiatives to address the challenges the Johnsons face, helping consumers build their financial capability through savings, credit building, and coaching. Through trial and error, practitioners have developed valuable insights about how to help consumers behave in ways that lead to better financial outcomes, such as more savings and better credit scores.

Still, the question remains, to what end? There is little clarity about the desired ultimate outcome, beyond the bigger savings balance and improved credit score. For some, the ultimate outcome is alleviating poverty. Yet the data show that the challenge extends beyond the poor, and beyond income. This lack of agreement on optimal outcomes has made it challenging to measure the success of financial capability initiatives. In turn, it is difficult to know which interventions are successful and deserving of greater investment and expansion. This issue plagues not only nonprofit practitioners in the asset-building and financial capability fields, but also private sector providers of financial services and the policymakers who set the ground rules for the marketplace.

But now, with more data in hand, practitioners and financial services providers have a new opportunity to connect their work on the ground to a broader vision for and definition of success that reflects the current realities of Americans’ lives. A common goal and a new framework for improving household financial outcomes — one that is broad enough to transcend fields and industries — will enable the complicated universe of government, the private sector and the nonprofit community to work in greater concert, and therefore, to achieve greater impact.

We believe success should be defined as greater consumer financial health and well-being.

A Framework for Financial Health

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), in an effort to create a framework for measuring the success of financial education, has defined financial well-being as “a state of being wherein a person can fully meet current and ongoing financial obligations, can feel secure in their financial future, and is able to make choices that allow enjoyment of life.” In “Financial well-being: The goal of financial education,” the CFPB goes on to identify four central elements of well-being: 1) control over day-to-day, month-to-month finances; 2) capacity to absorb a financial shock; 3) financial freedom to make choices to enjoy life; and 4) being on track to meet financial goals.

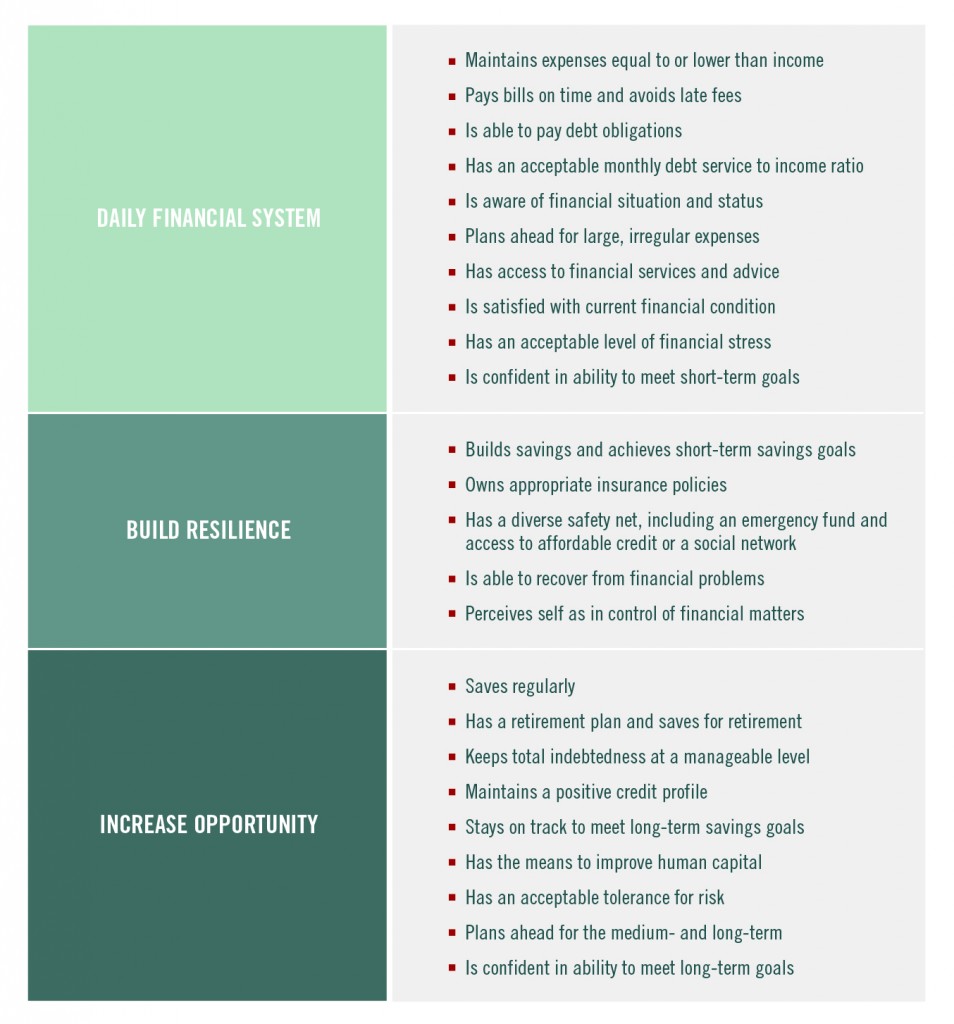

CFSI has been developing a similar success framework for financial health, which we define as when daily financial systems help individuals build resilience and increase opportunity. Table 1 includes the range of indicators we have identified for financial health.

Although the specific language of the CFSI and CFPB definitions differs, the concepts are fundamentally the same. Financial health and well-being is about pursuing dreams and reducing stress. The products and tools individuals use daily and their choices and decisions either help or hinder them in their quest.

A consensus that financial health and well-being is the right path forward is beginning to emerge across government, the private sector, and the nonprofit community. The CFPB has documented growing agreement that financial well-being should be the ultimate measure of success. Financial services firms, both established and new, are experimenting with ways to deliver products and services to help their customers measure, track, and improve their financial health. Leaders in the global financial inclusion community are beginning to explore whether financial health is a useful framework for understanding and measuring success.

Actors beyond the financial services and capability arenas are beginning to recognize the link between their success and the financial success of their customers and stakeholders — as discussed in many of the essays in Part 2 of this book. As Staples’ experience demonstrates (see Regis Mulot’s essay in this volume), employers across a variety of sectors are introducing financial wellness initiatives to improve productivity and satisfaction. Jason Purnell in his essay shows how the public health community is exploring financial health as a factor in broader health outcomes. Regina Stanback Stroud describes how community colleges are realizing that, to improve college completion rates, they must focus on the financial needs and challenges of their students. Treasury Deputy Secretary Sarah Bloom Raskin reports that the federal government is focusing on rising levels of student debt because it sees the connection between the financial health of Millennials and the health of the broader economy.

Most people have a gut sense of what financial health looks and feels like, but it is a complicated concept to define and measure. Financial health is fluid and dynamic, representing a continuum from poor financial health to good. Achieving and maintaining financial health is a lifelong journey. Even with the new data that now exist, there is still more to know about how families move along the continuum or about the pace of and breaks in their travels. There is also still more to understand about how the experience differs for people of color or for the very poor. Although it is a safe bet that lifecycle plays a part, the data suggest that people may experience financial shifts throughout their lives. To complicate matters further, financial health is not entirely an objective matter. Individuals have different life goals and different personalities. Financial health does not look exactly the same for everyone, nor does the path to achieving it.

Moreover, as the essays by Ray Boshara and authors in Part 3 of this book demonstrate, whether and how individuals achieve financial health depends greatly on the broader environment and institutional structures available to them. Imagine the immigrant who does everything right but cannot qualify for a car loan or a mortgage because she lacks a formal credit file. In this case, the lending institution’s practices are blocking the path to financial health.

What is missing is an agreed-upon set of financial health metrics. Building these metrics will require balancing the need for a point-in-time snapshot of families’ status with the benefits of a longer term perspective. It will require balancing the value of objective and subjective data, and considering both consumer and institutional needs and opportunities. Yet building the metrics is crucial. With metrics in hand, consumers will be more likely to get the information and insight they need to play their part in improving their own financial health. Nonprofit providers will have the framework they need to ensure their programs are succeeding in helping clients reach the right end goal. Private-sector companies can be challenged to hold themselves accountable for their contributions to the financial health of their employees, their customers, and their stakeholders. Finally, governments can be encouraged to see themselves as having an affirmative responsibility to improve the financial health of their citizens and provide a blueprint for the kinds of policies to enact, especially for American families like the Johnsons who struggle the most.

More Than Just Words: A Shared Vision Across Fields

The first step in designing and applying financial health metrics is to encourage cross-sector information sharing and conversation, which begins in the pages of this book and, hopefully, sparks an even broader dialogue. Different efforts are addressing different strands of the same problem. Developing a shared view about how to define the ultimate goal is critical in ensuring that the whole of the work is greater than the sum of its parts.

Practitioners, providers and policymakers who engage in this dialogue will need to resist the natural temptation to just “get on with it,” adopting new semantics before achieving a shared understanding of the ultimate goal. Whether our individual work is anchored in workforce development, community development, asset building or financial capability, we need to complete the hard work of defining the appropriate metrics through which we can each be held accountable. If these metrics are anchored sufficiently in financial health and well-being, they will transcend the specific sector from which we each hail.

Words matter, but the promise of financial health and well-being is more than just new words to describe what we each do. This new paradigm offers a blueprint for how each of our efforts contributes to the overall stability, resilience and upward mobility of American families. Understanding what we each have to offer, in the context of other actors and other fields, is critical. The magnitude of the challenges Americans face, coupled with the questionable future of the economy and our broken political system, demand that we leverage our mutual efforts as much as possible if we are to succeed in moving all Americans toward financial health.

While finding common cause in a clearly defined and measurable outcome is an essential foundation for the work ahead, getting there requires a diversity of approaches and perspectives. The history of the asset-building and financial capability fields demonstrates just how much we are still inventing and learning, and how important it is to keep going, even when we do not know all the answers. Our collective experimentation will be much more powerful if we can all agree that what we are ultimately aiming for is consumer financial health and well-being.

Thea Garon of CFSI provided invaluable assistance in writing this chapter.

NOTES

- For more information on the Diaries and the Johnsons, see www.usfinancialdiaries.org.

- The CFHS segmented households into seven categories based on the strength of their day-to-day financial system, their level of financial resilience, and how well positioned they were to pursue financial opportunities. The seven segments were bundled into three groups: healthy, coping, and vulnerable.